Arlington's African American Communities

Since its earliest suburban development, Arlington was made up of diverse neighborhoods, each with divergent, competing visions for the area’s future. Some of the oldest of these neighborhoods were African American neighborhoods. Their community planning traditions highlight the important role the process of suburbanization played in black community development. The continued presence of Arlington’s black communities and their impacts on the county as a whole shows how black visions of suburbanization played a role in the area’s development.

Green Valley was Arlington’s earliest black community. Its roots can be traced back to the 1840s. In 1844 Sarah and Levi Jones purchased fourteen acres of land to farm and build a home. Their property lay in southeastern Arlington on a hill overlooking Four Mile Run. On this land they grew oats and corn, had a large peach orchard of fifty trees, and built a barn and dairy house for their animals. Immediately following the Civil War, Green Valley quickly emerged as a middle class African American community. It became the largest community in terms of both geography and population by 1900. The strength of Green Valley was due, in large part, to the presence of the Jones family who subdivided and sold land to African Americans and encouraged the development of community institutions. Today Green Valley is known as Nauck.

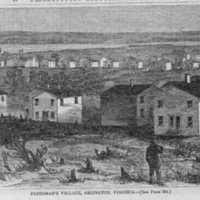

On December 4, 1863 the War Department opened Freedman’s Village contraband camp. The Village encompassed more than 1,100 acres of picturesque land in the northeastern portion of the county. Here, the government created a pre-planned community with houses, roads, and institutions as a physical representation of federal goals of moral uplift for the formerly enslaved population. Here the War Department, aid societies, and Villagers together built schools, churches, and fraternal organizations. The government erected 100 white washed, one-and-a-half story duplexes in a pared- down version of the Classical Revival style. Initially chosen by the War Department, this housing type was embraced by black Arlingtonians. They took great care in the maintenance and upkeep of these homes. When building their own homes later residents often recreated this style.

Though it was the county’s largest, Freedman’s Village was not the only black community to emerge in Arlington in the 1860s. In 1865 the Hall’s Hill community began to take shape. Located atop a hill in the western portion of the county, the land was once owned by prominent white landowner Bazil Hall. During the Civil War Hall suffered great losses to his property and finances, spurring him to sell land following the war’s end. New arrivals of African Americans seeking to make lives for themselves for the first time in freedom took advantage of this situation. Aided by the creation of black community infrastructure by the War Department through Freedman’s Village, African Americans in Arlington were more forward-looking than whites when it came to carving out communities throughout Arlington. Arlington moved slowly towards more concentrated communities of smaller land holdings, with Hall’s Hill as an intermediary step with many Hall’s Hill residents were working class who used their land for small scale subsistence farming. Residents also created the Calloway United Methodist Church and the Hall’s Hill school soon after the community’s creation.

In 1900 the combined forces of land developers, federal institutions, and local white land owners came together to close Freedman’s Village. These groups argued that the Village was a slum, despite residents taking great care to maintain their homes, farms, and social and cultural organizations.

As a result of this closure the Village’s African American residents and their community institutions spread across the county in the Freedman’s Village diaspora. The existing communities of Green Valley and Hall’s Hill expanded, while new communities and enclaves were formed. One of these new communities was the middle class community of Johnson’s Hill. It was founded in 1880 on a hill along Columbia Pike, near both Arlington National Cemetery and Fort Myer. Early settlers included Harrison Green, Emmanus Jackson, and Harry W. Gray. These men were leaders in the African American community, helping to found the important United Order of Odd Fellows fraternal organization in the neighborhood. Today Johnson’s Hill is known as Arlington View.

Another community founded due to the close of Freedman’s Village was the working class community of Queen City. Together with the adjacent community of East Arlington, Queen City was located in south-eastern Arlington on flat land, prone to flooding from the nearby Potomac River, near several factories and along the Washington, Alexandria, and Mt. Vernon trolley line. Queen City was built around the Mt. Olive Baptist Church which had roots in Freedman’s Village. Saving one-fourth of an acre for the church, the remaining land was parceled into forty lots to be sold to church members leaving the Village. With small plots of 20 feet by 92 feet, this subdivision transformed the former farm land into a more dense and suburban environment. Many of the homes constructed by former residents of Freedman’s Village at this time were reminiscent of the simple clap-board houses they called home in the Village, making housing type another product of the Village’s diaspora.

By 1942 more than 200 working class families lived in modest but well-kept frame houses. Just as was the case in Freedman’s Village, where residents saw a thriving community, outsiders saw the black neighborhood as a ghetto. In January of 1942 construction began for the Pentagon’s road networks in the path of the communities. Properties were seized through imminent domain laws with modest payments. With this loss some community members left the area entirely, while other residents and institutions relocated to Arlington’s remaining black communities of Hall’s Hill, Johnson’s Hill, or Green Valley.