Browse Items (41 items total)

In 1941 the Defense Homes Corporation (DHC), a subsidiary of Roosevelt's National Housing Agency, purchased 322 acres to develop housing for war-time personnel. Named Fairlington, the community featured 3,449 garden apartments. It was the largest project undertaken by the DHC and was the largest apartment complex in the nation upon its completion.

Designed by architects Kenneth Franzheim and Allen B. Mills, the community features Colonial Revival brick buildings which incorporate shared green space and non-grid cluster patterns in building layout.

After the war Fairlington transitioned from public to private ownership and was successfully converted to a condominium community. Despite a proposal to level the community in favor of high-rise housing in the 1960s, Fairlington remains Arlington's largest selection of moderate-income housing.

Designed by architects Kenneth Franzheim and Allen B. Mills, the community features Colonial Revival brick buildings which incorporate shared green space and non-grid cluster patterns in building layout.

After the war Fairlington transitioned from public to private ownership and was successfully converted to a condominium community. Despite a proposal to level the community in favor of high-rise housing in the 1960s, Fairlington remains Arlington's largest selection of moderate-income housing.

Collection: Neighborhoods

In 1942 the federal government created emergency wartime housing to assist African American residents from Queen City displaced by the construction of the Pentagon. They constructed a trailer camp on mud flats on the outskirts of the Green Valley neighborhood. Entire families squeezed into trailers equipped with stoves for heat and cooking, convertible couch-beds meant to sleep four people, and no running water. The trailer camp was closed shortly after the war.

Collection: Neighborhoods

In 1942 the Office of War Information photographed suburban homes under construction in Arlington. Arlington saw a huge boom in building during the war years as civilian and military federal employees came to work in Washington and the newly constructed Pentagon. This housing boom profoundly changed the make up of Arlington.

Collection: Neighborhoods

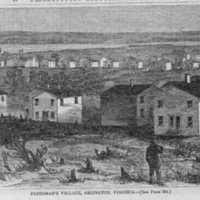

This woodcut, featured in Harper's Weekly in 1864, depicts Freedman's Village. A contraband camp established on the grounds of Arlington House, Robert E. Lee's plantation, Freedman's Village was Arlington's first all black community as well as its first successful pre-planned community. Here formerly enslaved men, women, and children learned trades, attended school, established churches, and create a thriving African American community. When the Village was formally closed by the federal government in 1900 it lead to the establishment of many other black communities in Arlington through the Freedman's Village diaspora.

Collection: Neighborhoods

Here a trolley car from the Washington, Arlington, and Fall's Church Railway line approaches the Lacey Station in Ballston. Trolley lines helped further growth of Arlington's late-eighteenth century communities, like Ballston, as well as the nearly two dozen new nineteenth century communities. They helped to spur the development of Arlington as a suburban enclave of Washington, D.C. by providing easier access for commuters.

Collection: Neighborhoods

The Lacey Station was one of the stops used for the Ballston community on the Fairfax Line of the Washington, Arlington, and Fall's Church Railway. In the nineteenth and early-twentieth century trolley and railway development expanded commuter travel, encouraging and reacting to a rising commuter community in Arlington County.

Here, Carl Porter and his family are pictured at the station in 1906.

Here, Carl Porter and his family are pictured at the station in 1906.

Collection: Neighborhoods

Levi Jones and his wife Sarah were two of the earliest settlers of Green Valley, today known as Nauck.

In 1844 the couple built a 14' x 16', two story log cabin. During the Civil War, federal troops destroyed their original home. But following the war they were able to rebuild, creating the home pictured here.

The Jones were influential community leaders. Before other accommodations could be made, they hosted church services in their home. They sold land to freed slaves following the Civil War. These sales, along with interest from Washington, D.C. land speculator John Nauck, a white businessman who sold land to African Americans in the Green Valley area, strengthened and expanded the black community there. Their impact on Nauck's black community continued into the twentieth century, when the federal government built the Paul Dunbar Homes on 11 of their original homestead in 1942.

Levi and Sarah had two sons, Levi and Isaac, and three daughters, Mary, Martha, and Louise. Levi died in 1886 and Sarah followed in 1913 at the age of 95. They are buried at the Lomax AME Cemetery.

In 1844 the couple built a 14' x 16', two story log cabin. During the Civil War, federal troops destroyed their original home. But following the war they were able to rebuild, creating the home pictured here.

The Jones were influential community leaders. Before other accommodations could be made, they hosted church services in their home. They sold land to freed slaves following the Civil War. These sales, along with interest from Washington, D.C. land speculator John Nauck, a white businessman who sold land to African Americans in the Green Valley area, strengthened and expanded the black community there. Their impact on Nauck's black community continued into the twentieth century, when the federal government built the Paul Dunbar Homes on 11 of their original homestead in 1942.

Levi and Sarah had two sons, Levi and Isaac, and three daughters, Mary, Martha, and Louise. Levi died in 1886 and Sarah followed in 1913 at the age of 95. They are buried at the Lomax AME Cemetery.

Collection: Neighborhoods

Bungalow homes, like this house in the Cherrydale neighborhood, were very popular in Arlington during the early twentieth century. The main characteristics of these homes are that they were one story with large front porches and sloping roofs. Bungalows came into fashion during the Progressive Era, as more ornate Victorian homes and ideals were rejected in favor of the simpler Bungalow style which pushed connection to nature, simplicity, and honesty. By WWI this was the most common housing type nationally and in Arlington.

Many of Arlington's Bungalow houses were purchased through the Sears Roebuck mail-order catalog. The practice of ordering homes through mail-order was more popular in Arlington's white neighborhoods than its African American neighborhoods. Sears houses could be found in not only Cherrydale, but also Clarendon, Lyon Village, Maywood, Lyon Park, Ashton Heights, Alcova, Aurora Hills, and Virginia Highlands. This home appears to be in "The Vallonia" style.

Many of Arlington's Bungalow houses were purchased through the Sears Roebuck mail-order catalog. The practice of ordering homes through mail-order was more popular in Arlington's white neighborhoods than its African American neighborhoods. Sears houses could be found in not only Cherrydale, but also Clarendon, Lyon Village, Maywood, Lyon Park, Ashton Heights, Alcova, Aurora Hills, and Virginia Highlands. This home appears to be in "The Vallonia" style.

Collection: Neighborhoods

In May of 1942, U.S. Farm Security Administration photographer John Collier took pictures of homes and subdivisions under construction in Arlington, Virginia. Arlington saw a great deal of construction during World War Two as new homes and new neighborhoods were created in Arlington Heights, Green Valley, Fairlington, and more for war workers flocking to Washington.

Collection: Neighborhoods

In 1913 the Navy erected three huge radio towers at the intersection of Columbia Pike and Courthouse Road, between the two African American communities of Johnson's Hill and Butler-Holmes. These radio towers, called the “three sisters,” were marvels of modern communications technology and engineering in their time. They were the tallest man-made structures in the world upon their completion in 1913, towering over local pillar the Washington Monument. In 1915 they transmitted the first trans-Atlantic voice communication to the Eiffel Tower.

The towers were removed in 1941 because they obstructed flight-paths for the newly constructed Washington National Airport.

The towers were removed in 1941 because they obstructed flight-paths for the newly constructed Washington National Airport.

Collection: Neighborhoods