Browse Items (13 items total)

The American Nazi Party was founded in Arlington County in 1958 by George Lincoln Rockwell. Rockwell was born in Bloomington, Illinois in 1918, educated at Brown University and the Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, and served as a Navy pilot in WWII and Korea. Inspired by Hitler, Rockwell blended German fascism with American racism. He and his organization protested local and national Civil Rights activities, picketed businesses, and held white-pride events. They were also very active in politics. In this photo Rockwell attends a School Board meeting to work again school integration. He was assassinated in Arlington in 1967 by fellow Nazi party member John Patler over control of the organization.

Collection: Civil Rights

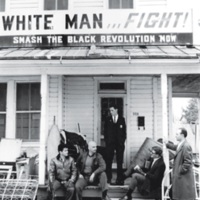

The American Nazi Party was founded in Arlington, Virginia by George Rockwell in 1958. The group was headquartered out of Arlington's Ballston neighborhood. The Arlington chapter had 50 to 60 members active in the late-1950s and early-1960s. From this headquarters the group organized protests, demonstrations, and political activities. In this photograph, Nazis sit on the front porch of their offices on Randolph Street, purchased for them by Floyd Fleming.

Collection: Civil Rights

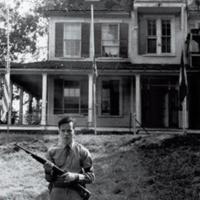

The American Nazi Party was founded in Arlington County by George Rockwell in 1958. The Arlington chapter of the American Nazi Party had 50 to 60 members active in the late-1950s and early-1960s. Most of these members lived together in a late-Victorian home they used as a barracks on Wilson Boulevard in Clarendon. Local sympathizers not directly affiliated with the group showed their support by bringing the men food to this home during the winter. While some residents complained of the “sieg heil” salutes given by their new neighbors in greeting, the Nazis did not actually break any community or county laws. Many came to call this property "Hatemonger Hill."

Collection: Civil Rights

At the turn of the last century baseball was such a popular sport in Arlington that the county supported as many as five semi-professional teams. Like most elements of life at the time, sports and recreation were segregated.

Beginning in the 1910s, Arlington's black community formed the Black Socks Baseball team, pictured here. From their home base of Peyton Field in the Nauck community (formerly Green Valley). the Black Socks toured the east coast playing other black teams.

Beginning in the 1910s, Arlington's black community formed the Black Socks Baseball team, pictured here. From their home base of Peyton Field in the Nauck community (formerly Green Valley). the Black Socks toured the east coast playing other black teams.

Collection: Community Institutions

In 1946 Arlington's African American community leaders began fundraising for the Veteran's Memorial Branch YMCA. Recreational facilities, including those sponsored by the existing YMCA, were segregated along racial lines at the time. Spearheaded by life-long activist and community resident Edmund Fleet, the Veteran's Memorial Branch YMCA opened in 1949.

It sponsored social and recreational activities for Arlington's black youth. In the 1960s, a pool was added to the facility so Arlington's black youth would finally have a safe place to swim in the county. This photograph shows the groundbreaking for the swimming pool.

It sponsored social and recreational activities for Arlington's black youth. In the 1960s, a pool was added to the facility so Arlington's black youth would finally have a safe place to swim in the county. This photograph shows the groundbreaking for the swimming pool.

Collection: Community Institutions

During World War Two the federal government created six segregated barracks style wartime emergency housing neighborhoods. One of these facilities was the 11-acre Paul Dunbar Homes complex in the Green Valley community, today called Nauck.

Here 86 African American households build a community. Following the war, Arlington officials wanted to tear the neighborhood down. Dunbar residents created the Dunbar Mutual Homes Association which they used to pool their resources, secure a loan, and turn Dunbar Homes into a community dedicated to providing affordable housing. Dunbar Homes was demolished in 2005 to make way for luxury town-homes.

Here 86 African American households build a community. Following the war, Arlington officials wanted to tear the neighborhood down. Dunbar residents created the Dunbar Mutual Homes Association which they used to pool their resources, secure a loan, and turn Dunbar Homes into a community dedicated to providing affordable housing. Dunbar Homes was demolished in 2005 to make way for luxury town-homes.

Collection: Neighborhoods

During the 1920s Arlington had a bathing beach on the Potomac River. The beach featured swimming, concessions, canoes, and a ferris wheel. Despite being located near the African American neighborhoods of East Arlington and Queen City, the Arlington Bathing Beach was segregated. Here you can see all-white bathers enjoying the facility. James "Jimmy" E. Taylor, who lived in Hall's Hill, said that black children swam in a "creek out on Route 50... called 'Blue Man Junction'" since more formal swimming locations were not open to them. The beach was closed down in 1929 to make way for expansions to Hoover Airport, today known as National Airport.

Collection: Community Institutions

During the 1920s Arlington had a bathing beach along the Potomac River, near the present-day Pentagon. A 1923 brochure for the beach hoped to entice visitors from Washington by highlighting "parking facilities such as are seldom found." The beach featured swimming, concessions, canoes, and a ferris wheel. Despite being located near the African American neighborhoods of East Arlington and Queen City, the Arlington Bathing Beach was a segregated whites-only environment. It was closed down in 1929 to make way for expansions to Hoover Airport, today known as National Airport.

Collection: Community Institutions

Luna Park was an amusement park in Arlington County in operation from 1906 to 1915.

The Park was owned and operated by the Washington, Alexandria, and Mt. Vernon Railway Company. The Company commissioned Ingersoll Company of Pittsburgh to build the park after Arlington Prosecutor Crandal Mackey closed Arlington's gambling houses. Fearing a drop off in patronage on their line, Luna Park was meant to act as a more family friendly draw. The Park featured water rides, side shows, and animal acts.

The architecture of the venue was Ionic. The style also had many international inspirations, including Egyptian, Byzantine, Moorish, Japanese, Arabic, Gothic, French, Renaissance, and Corinthian designs.

Like almost all recreation activities in Arlington at the time, Luna Park was segregated.

The Park was owned and operated by the Washington, Alexandria, and Mt. Vernon Railway Company. The Company commissioned Ingersoll Company of Pittsburgh to build the park after Arlington Prosecutor Crandal Mackey closed Arlington's gambling houses. Fearing a drop off in patronage on their line, Luna Park was meant to act as a more family friendly draw. The Park featured water rides, side shows, and animal acts.

The architecture of the venue was Ionic. The style also had many international inspirations, including Egyptian, Byzantine, Moorish, Japanese, Arabic, Gothic, French, Renaissance, and Corinthian designs.

Like almost all recreation activities in Arlington at the time, Luna Park was segregated.

Collection: Community Institutions

Non-Violent Action Group (NAG) activists Dion T. Diamond (left) and Laurence Henry are arrested by Arlington Police Sergeant Roy G. Lockey (left) and Lt. Ernest A. Summers. The two were arrested while demonstrating at the Howard Johnson's restaurant in Arlington.

This scene was a part of a coordinated sit-in movement which occurred across several Arlington lunch counters in June of 1960 to protest segregated accommodations. These demonstrations ultimately led to the integration of restaurants in Arlington. But unfortunately this did not end racism. African American resident Princeton Simms recalled that despite integration proprietors would “pick up the plate and throw it in the trash” after they were used by black patrons. This kind of outward hostility meant many black customers continued to prefer to patronize black owned restaurants despite integration.

This scene was a part of a coordinated sit-in movement which occurred across several Arlington lunch counters in June of 1960 to protest segregated accommodations. These demonstrations ultimately led to the integration of restaurants in Arlington. But unfortunately this did not end racism. African American resident Princeton Simms recalled that despite integration proprietors would “pick up the plate and throw it in the trash” after they were used by black patrons. This kind of outward hostility meant many black customers continued to prefer to patronize black owned restaurants despite integration.

Collection: Civil Rights